Standing under the border wall, Jose tells me, "somos ni de aqui, ni de alla. We are neither from here nor there."

July 3, 2008, Tijuana- Today I’m walking with Dan along Avenida Internacional, the four-lane highway that runs along the border between Tijuana and San Diego, and I cringe as I feel the rush of speeding cars at my back, dragging on my body. I know we are far enough off the road, but it’s a little unnerving.

I’m getting a sense, if only briefly, how the migrants feel as they navigate an urban landscape so hostile to the solitary walker.

Here at the border fence, the intoxicating charms of nature yield to rough iron I-beams and massive plates of rusted iron, once hastily welded together as a makeshift barrier, now become a permanent blight on the landscape. The detritus of acts of violence long past, the “primary fence” separating San Diego from Tijuana is constructed from Vietnam aircraft landing mats.

Our reveries are interrupted by the drone of traffic and car horns, the rocks and natural greenery littered with mounds of jagged chunks of cement, dead branches, abandoned pieces of carpet, old TVs, scattered clothing tangled in white plastic bags, the stubborn green fronds of a fennel plant jutting out through the springs of an overturned sofa. We’re here to get a view of the DHS border fence construction from the Tijuana side.

Avenida Internacional ascends to the top of a high mesa, and from this vantage point we can see the original staging area–Area 5–for the construction of this last segment of the triple fence, slashing an 800-ft-wide scar into the land for 4.5 miles from here to the Pacific ocean. Down below, we can see a bright yellow tanker truck bearing the Keiwit Corporation logo, a mining company out of Omaha, Nebraska awarded a $48.6 million contract this year to complete the construction. That’s a little more than $10 million per mile, not including cost overruns, for those of you who are counting.

Ni de aquí, ni de allá

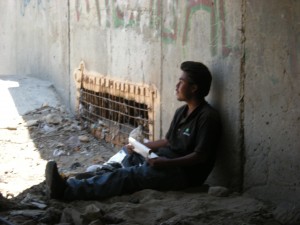

Up ahead we see a massive drainage culvert where winter rains bring toxic runoff, trash, and silt under the road and drain into the Tijuana estuary’s coastal sage scrub. Dan easily leaps down, landing safely on an old tractor tire–I have more trouble making the 6 foot drop, and go skidding on my hands and knees in the dirt. Suddenly I see why Dan has come down here: I see two young men, then four, then five, lurking in the shadow of the massive concrete retaining wall. Two men duck into the long tunnel as we arrive, while a teenager wearing a bright red nylon soccer jersey watches us climb down the wall. These men live here, directly under the rusty barrier wall, trapped in between the US and Mexico. Without papers, these migrant workers can end up in limbo for months, neither welcome to return to jobs and communities in the United States nor able to enter Mexico.

Fearful at first, the men warmed up to us as Dan sat down on an old beat up metal computer case, opened his Macbook to record his interview with the men, and began chatting.

“So, how long have you guys been waiting down here?”

A man stretched out in the shade on a grey urethene auto upholstery cushion, answered,

“Pasé dos dias en la cárcel, y un mes aquí.”

He had been waiting here in the culvert for one month, after being in jail for two days. Today he was waiting for the sun to go down so he could make another attempt to cross back into the US.

Another man, wearing a blue windbreaker, layered t-shirts, and a navy blue baseball cap, told us with some hestitation, that his name was Jose. He reached up and put his hands above him on the border fence. “Ni de aquí, ni de allá.” We’re neither here nor there.

“Es mejor cruzar que regresa a México,” the man on the cushion explained. In Mexico, police patrol the area around the culvert, harassing and often arresting the men for vagrancy. Crossing back into Mexico is fraught with risk, and without friends in Tijuana, you can’t make it. He told us his name, which I will say was Francisco A., and he had lived for eight years in Seattle, working as a roofer, until last month, when he was deported–to Ciudad Juarez, just across the border from El Paso, Texas. He just wanted to go back to Seattle.

Another man who sat leaning against the far wall, reading a book, responded with a similar story. He had been stuck here for four months now, but works in Escondido, in northern San Diego County. Four months earlier he had been deported–and they took him all the way to Nogales, on the Arizona-Sonora border.

Another man who sat leaning against the far wall, reading a book, responded with a similar story. He had been stuck here for four months now, but works in Escondido, in northern San Diego County. Four months earlier he had been deported–and they took him all the way to Nogales, on the Arizona-Sonora border.

“Es muy caliente cruzar in Nogales,” he explained. “It’s really too hot to cross in Nogales.”

Indeed, one of the effects of Operation Gatekeeper in San Diego and Operation Hold the Line in El Paso, efforts begun in 1994 and which focused on reinforced border fencing and increased border patrol in San Diego-Tijuana and Juarez-El Paso areas, has been to push immigrants into more treacherous routes, through high desert with tempertures reaching upwards of 127 degrees, and rugged mountain passes where immigrants easily get lost and freeze to death.

The current ICE strategy–deporting Mexican migrants to regions far from their communities in the US–draws upon a long legacy of outrageous and unjust US immigration policy. In the 1950s, under Eisenhower’s “Operation Wetback,” municipal, county and state authorities working together with border patrol, performed sweeps of agricultural areas and Latino neighborhoods, setting target goals of 1000 arrests per day, and picking up US and Mexican citizens alike, then transporting them deep into Mexico before being freed. Many were put aboard ships and transported from Port Isabel, Texas to Veracruz.

The only difference today is that ICE is deporting migrants to even more dangerous border cities with rough, hostile terrain. Not only do the migrants have no family, friends or support network when they are dropped off in a strange, new city. They also arrive with no papers to prove their Mexican citizenship, and, as Francisco explained, they find that it is better to cross back into the US than to try to make their way in Mexico.

While fence supporters like Congressman Duncan Hunter crow that the border fence has reduced the numbers of migrants who cross into the US to find work, statistics show that migrants are merely crossing elsewhere. Six years after the establishment of Operation Gatekeeper, the other nine sectors of the 2000-mile border reported a 20% increase in the number of migrant apprehensions, while crossings in San Diego and El Paso dropped to less than one third of earlier levels. And an extremely high percentage of migrants succeed. According to a study by Wayne Cornelius, director of the Center for Comparative Immigration Studies at The University of California, San Diego, 92% of Mexican migrants trying to enter the US illegally eventually succeed.

Thousands are dying now, from heat exposure, freezing, and car accidents caused when border patrol agents engage in high speed chase with fleeing vehicles. A San Diego group called Border Angels has been working to put water tanks in the desert to help rescue lost migrants, but estimates are that between 4000 and 11,000 migrants have died trying to cross the desert since the beginning of Operation Gatekeeper.

And even those few who do cross in San Diego County face violence from border patrol agents.

“La migra nos tiran como conejos,” Jose explained. “They shoot at us like rabbits, and they hit us.” Jose removed his navy blue windbreaker and pulled back the sleeve of his t-shirt to show me a bruise on his shoulder.

In April of 2007, a surveillance video of a deadly shooting near Calexico was leaked to the internet, prompting the Mexican government to call for an investigation into the incident. On March 26, 2007, a young man, Ramiro Gamez Acosta, age 20, was shot once in the chest by a border patrol agent armed with a M-4 carbine and died within minutes.

Dressed in jeans, a white t-shirt, and solid running shoes, clutching a bright green 2-liter bottle of Sprite, Francisco looked prepared for the journey. His face still shielded by a straw cowboy hat, he gently asked us if we had any money.

“No uso drogas,” Jose assured me. “I don’t use drugs or anything. We are just trying to work.” Dan and I left them with five bucks, enough to get them a meal for the evening, but not much else. Then we climbed back out of the culvert and returned on our journey up the road.

Down below, we could see two of the men, surveying the horizon and looking for signs of border patrol from a spot way out on the the north end of the culvert. Foolishly we waved goodbye–we could just as well have sent up warning flares–and the men went running for cover.

“Oh, no, we shouldn’t have done that. Now they’re probably gonna get caught.” But after we had walked a while we looked back, and they were long gone.

“They hide really well, actually,” Dan remarked. No, we couldn’t see them at all.