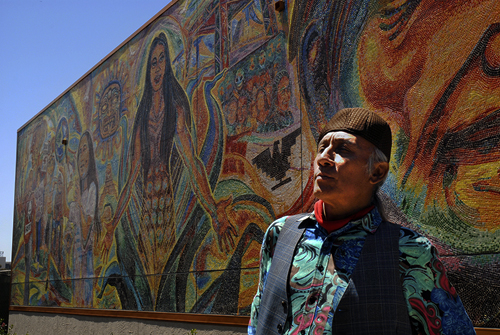

Mario Torero stands proud in front of the Chicano Legacy 40 años mosaic on Peterson Hall at UCSD. Photo by Jennifer Rubin www.cinemaviva.com

Originally published in San Diego CityBeat

May 24, 2011

by Jill Holslin

The UCSD campus can feel really gray. Widely celebrated for its cutting-edge architecture and world-class collection of conceptual art, the campus can also feel “too high-techie” and “too modern,” students say.

Concerned for years about low enrollment of students of color, some Latino students and faculty at UCSD worry that the dreariness of the campus might be part of what’s turning off prospective students from urban neighborhoods where colorful street art puts a bold stamp on the environment.

The newly completed “Chicano Legacy 40 Años” mosaic on a wall of UCSD’s Peterson Hall could change that. The result of two years of collaboration between internationally known, San Diego-based artist Mario Torero and students in UCSD’s Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA), the mosaic brings a vibrant splash of color to the campus.

But it also marks a more far-reaching achievement: As the first permanent art installation at UCSD to celebrate the history of a minority community, the mosaic pays homage to the oft-forgotten history of UCSD’s political activism and struggles for educational equality.

The mural depicts two local figures central to Chicano history at UCSD—Carlos Blanco Aguinaga, professor of literature and advisor to MAYA/MEChA in the late ’60s and early ’70s, and Gracia Molina de Pick, a native San Diegan, longtime educator and leader in the international feminist movement. Molina de Pick developed curriculum for the first Chicano-studies associate’s degree in 1970, and both were central to the establishment of Chicano studies at UCSD in the ’70s.

Forty years after the struggle of San Diego’s Barrio Logan community to establish Chicano Park, Torero sees the new piece as the culmination of a life’s work dedicated to the fusion of art and activism, calling himself an “artivist.”

For students like Bryant Peña, there are huge implications of a mosaic depicting local activism on a campus dedicated primarily to the sciences. Peña says it justified his decision to major in ethnic studies and visual arts.

“I remember walking up the hill and looking up at the mural, and it just stuck out among all the gray and transformed the space, and the sun was shining on it, and it was gorgeous,” Peña says. “It was a very validating experience. It said our identities really do exist and you can do what you believe in…. In a time when art is largely confined to the gallery, it is revolutionary to see that art in a public space. It creates a rupture in the everyday.”

But not everyone was ready for a revolution in public art on campus.

When Jorge Mariscal, professor of Literature and director of the Chicano/a Studies Program at UCSD, showed a small mockup painting of the Chicano mosaic to campus leaders, he says, some made sour faces and others said the Chicano content was “too old-school.” There wasn’t much enthusiasm for it.

“They didn’t get the mural tradition,” Mariscal says. “They didn’t get Chicano history; they didn’t get that the undergrads themselves wanted this….

“And the elephant in the room is, of course, the Stuart Collection,” Mariscal continued.

On a campus partly shaped by the internationalist, conceptual tone of UCSD’s public-art collection, Mariscal says, a Chicano mosaic seemed to be pushing the limits of what UCSD leaders thought the school was or wanted to be. By an agreement between art collector James Stuart DaSilva and UCSD in 1982, the Stuart Collection Advisory Board advises the UCSD chancellor on the selection of artists for all commissioned art on campus. While the university is now home to 17 works of contemporary sculpture created by world-class artists for the Stuart Collection, Latino faculty and students argued that the restrictive commissioning opened little space for public art reflective of San Diego or Chicano history.

CityBeat asked Mary Beebe, director of the Stuart Collection, whether her organization really exerts that much control over what kind of art is installed permanently on campus.

“We sort of do,” Beebe explains. “That’s part of the agreement with the university that the Stuart Collection set up. We have to protect the quality of the collection. If things of much lesser quality start popping up all over the place, then our artists are not going to want to put their work there. We don’t want to water down the campus. I know everybody wants art, but the agreement says that we get to decide what kind.”

For Mariscal, a mandate to protect the reputations of world-class international artists doesn’t necessarily conflict with other roles public art can play. He made his arguments but was repeatedly told the project would never be approved. Rather than give up, he kept pushing for the mosaic and campus-wide race-relations issues eventually worked in his favor.

Last year, tensions rose after a fraternity mocked Black History Month by sponsoring a racist-themed party called “Compton Cookout.” As part of the response, students in the Black Student Union voted to include the Chicano mosaic in their list of demands to the administration, and Mariscal continued to seek funding and support to make it permanent.

Mariscal found eager support from university Chancellor Marye Anne Fox and Vice Chancellor of Resource Management and Planning Gary Matthews, who, for the first time in decades, authorized a permanent installation independent of the Stuart Collection.

After a long search, Torero discovered a group of muralists in China, the Panyu Collective in Shanghai, who could create glass tiles for the mosaic, and the piece materialized in a matter of months.

Torero, an artist known for his colorful personality, credits the spirits for easing the conflict.

“So, on my own, I went to Chicano Park and did my earth prayers to Pachamama, and I brought some earth from Chicano Park and I sprinkled it in front of the wall at UCSD, in front of the banner,” Torero says. “And I did my chanting and I sent out the spiritual message for Pachamama to do her magic. And I left it as such. It’s just my way of giving things and uniting our cosmic forces. And sure enough, the miracle happened.”

See my photos on Flickr