Smuggler’s Gulch

Smuggler’s Progress: border wall construction in Smuggler’s Gulch between San Diego County and Tijuana, Baja California

Smuggler’s Gulch was a beautiful canyon, home to some of the most important and rare coastal scrub habitat in Southern California. This steeply sided, 180-foot deep canyon just below and west of Spooner’s Mesa is located at the southernmost border of San Diego, California on the international boundary with Mexico and 1.5-2 miles from the Pacific Ocean.

Smuggler’s Gulch is part of a 14-mile border infrastructure project in San Diego County sponsored by the Department of Homeland Security.

Today, Smuggler’s Gulch has been filled in to provide for a border patrol access road and a massive natural barrier against unauthorized border crossing, its natural role as a protective sediment basin disrupted by a massive berm And this project is one of many of over 600 miles of border walls and barriers built since 2008 in sensitive lands along the 2000-mile U.S.-Mexico border.

Today, Smuggler’s Gulch has been filled in to provide for a border patrol access road and a massive natural barrier against unauthorized border crossing, its natural role as a protective sediment basin disrupted by a massive berm And this project is one of many of over 600 miles of border walls and barriers built since 2008 in sensitive lands along the 2000-mile U.S.-Mexico border.

How did this come to be? In the local south San Diego geography that the border patrol calls “Areas 5 & 6,” a total of 180 acres of land was condemned by the federal government in 2008, (127 acres of county land and 53 acres of state park land), a long strip of land along the U.S.-Mexico border bordering the Tijuana River Valley Open Space Preserve, Border Field State Park, and the internationally recognized Tijuana River National Estuarine Research Reserve. Local environmental groups had spent four years in a legal struggle against the condemnation, headed by Imperial Beach resident Mike McCoy and public interest attorney Cory Briggs. The City of San Diego, in partnership with various regional and state agencies, had already invested over half a billion dollars in 20 years in land acquisition and improvement projects in the Tijuana River Valley, an astonishingly beautiful wetland reserve hosting 370 species of birds, many of them endangered, and a wide variety of habitats unique to the southern coastal region of the Californias.

According to the condemnation order, filed on April 25, 2008, the federal government awarded the State of California $919,000 dollars for the state land–just over $17,300 an acre, deemed “just compensation” in a market where nearby undeveloped industrial land sells for over $550,000 an acre. Although the condemnation order granted California State Parks the right to contest the amount of compensation, the state made no move to intervene.

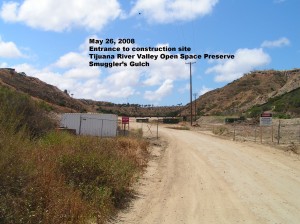

In May 2008, the construction began, headed by contractor Kiewit of Omaha, Nebraska. Contractors began by laying an enormous 300-foot culvert to allow the continued flow of water and sediment through the canyon.

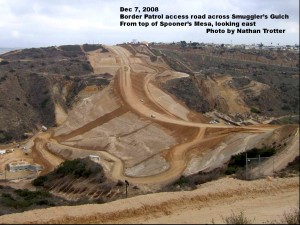

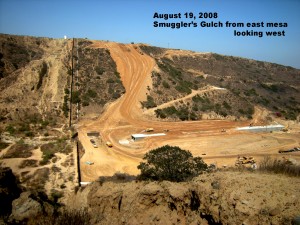

In July-Sept the U.S. section of the canyon was completely filled in with 2.2 million cubic yards of soil and rock, creating a 145-foot high berm across which runs a fenced corridor with a road to allow border patrol vehicle access along two sides of a high wall. The total footprint of the berm is four tenths of a mile long, and from ridge to ridge, it is a quarter mile across. The canyon was once half a mile long from the international boundary to the north end on Monument Road.

The berm was created from soil and rock cut from the tops of the two mesas on either side of the deep canyon. Cutting and earthmoving was done throughout the summer of 2008, and the berm was in place by the late fall.

The berm was created from soil and rock cut from the tops of the two mesas on either side of the deep canyon. Cutting and earthmoving was done throughout the summer of 2008, and the berm was in place by the late fall.

Precious natural habitat

The canyon is home to some of the most important habitat in the Southern California region. The last stand of Maritime succulent scrub grows here, found nowhere else in the US, and the area hosts the northernmost extent of this habitat, which extends southward into Mexico. The Coastal sage scrub of the area is a very important habitat for federally listed endangered birds. The project has directly destroyed some very important habitat in the Tijuana Estuarine Research Reserve directly north of the canyon. The footprint of the berm now fills in half the length of the original canyon, greatly reducing its capacity to serve as a de facto sediment basin protecting the estuary and ocean water from pollutants and sediment build up according to Clay Phillips, of California State Parks.

To facilitate the natural flow of storm water through this long canyon, a culvert was built as part of the infrastructure project.

According to land manager Oscar Romo, the culvert is now adding energy to the water—instead of running gently through boulders and land, the water now shoots through the smooth concrete of the culvert. The water gains momentum, and has a lot of energy by the time it reaches the channel on the north side of Monument Road, resulting in the flooding of ranches.

As Program Manager of the Tijuana River Estuarine Research Reserve, Romo knows this region well. He notes that the the geography of this small area adds to the momentum of the travelling water—water runs into the U.S. from Mexican canyons that are 750 feet above sea level into a culvert at 20 feet above sea level and then out to the estuary. It needs only a flat, smooth surface to make it run faster. After construction of the berm, water is now coming from areas that in the past never brought water. Romo argues that there is a lot of evidence that the berm is causing rechanneling of the water into new pathways and directions.

Soils in this area erode easily when stripped of plants and delicate, intertwined root systems that have taken tens of thousands of years to develop. Deep rilling is visible on the walls of the canyon, and massive erosion and a deep crack was visible on the berm after brief winter rains in December 2008.

One reason for this erosion is that the contractors used soil & rock materials that didn’t match the original soil. The top part of Spooner’s Mesa has a different soil composition than the canyon floor below, and the contractors filled the canyon by stripping soil from the top of the mesa and using this soil to build the berm. The entire area was created by layers of flooding over millions of years. When soil is displaced in this way, the top layer, which is mostly sealed, comes into contact with other layers and cracks will develop.

In December of 2008, a deep joint was visible from the top to the bottom of the berm (visible in the photo here covered with plastic tarp). According to Romo, the contractors didn’t fully consider the specific climate and rain conditions in south San Diego County and integrate that into the project. The rainy season is short, and when it rains, it rains all in one night. In San Diego construction, those joints are usually created differently using different methods to drain. In this case, Romo noticed no adjustment to these special conditions—the contractors allowed these two types of soil merge, dragging soil from the mesas into the canyon, but they never studied the way that was going to interact with rain. The crack was caused because the water needed a place to go—the water coming from the two mesas on either side of the berm was flowing down through this crack. In the spring of 2009, to adjust to these conditions, Romo noted that the contractors began to make changes in the geometry of the road.

One continuing problem is that there is no adequate sediment monitoring program in place. The installation of sensor would allow for the measurement of the velocity and strength of the water. say Clay Phillips and Oscar Romo. Federal promises of mitigation and maintenance have been slow to materialize.

The sides of the berm were seeded after construction, but by fall 2009 the DHS was taken to task by Representative Susan Davis for failure to provide sufficient irrigation to complete the project. Davis submitted a letter to DHS Secretary Janet Napolitano requesting “immediate action be taken to protect the surrounding environment as was promised to Davis and the San Diego community.” In this letter, Davis pointed out, “These conditions are unacceptable, and the bare slopes are an illustrative example of the lack of foresight in mitigating the environmental effects of the Border Infrastructure Project.” …“We are seeing the results of what happens when it becomes the policy to waive environmental laws,” said Davis, whose congressional district is home to the project in question. “Not only has the entire character of Smuggler’s Gulch been irrevocably altered, but it now threatens other habitats.” (Susan Davis Press Release, 28 Oct 2009).

The DHS project received a volley of criticism after the Final Environmental Impact Statement was released in July 2003. The California Coastal Commission filed a report critiquing the project, and a lawsuit filed in 2004 argued that the federal EIS did not take into account any of the specific qualities or features of the San Diego topography, but was merely a “generic” EIS for the entire border.

The list of critics includes the Department of the Interior, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the City of Imperial Beach, the City of San Diego, the County of San Diego, the San Diego Association of Governments (SANDAG), the California Coastal Commission, the California Department of Fish and Game, the California Resources Agency, the California Department of Parks and Recreation, and the California Coastal Conservancy and the following plaintiffs in the 2004 lawsuit: Sierra Club, California Native Plant Society, Southwest Wetlands Interpretive Association, San Diego Baykeeper, and Center for Biological Diversity.

Concerns about environmental damage continued to be voiced by state agencies throughout construction. In October 2008, the State Water Resources Control Board sent a letter to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, reiterating their concerns about the environmental impact of the Smuggler’s Gulch in-fill project, a major portion of the San Diego sector VI fence corridor (Letter in author’s archives). The letter cites statements of Michael Chertoff, indicating the commitment of DHS to actively solicit public input on the environmental impact of the project and to exercise good environmental stewardship throughout the construction process.

Yet, to date, the State Water Resources Control Board notes that they have not seen evidence that these commitments are being carried out. Upon inspection of the site, the board observed complete lack of temporary erosion control measures, failure to implement the storm water pollution protection plan, poor drainage and shoddy grading practices on construction access roads. In addition, there appears to be no post-construction maintenance plan, nor has DHS been forthcoming about funding such a plan. The board anticipates that a number of consequences will follow including severe erosion when winter rains begin, sediment spill and damage to the estuary, high environmental costs in the form of lost hydrological function in the watershed, and expensive remedial maintenance costs which will no doubt be borne by local, county and state agencies.

Perhaps most ironic, the board notes that these problems will create hazards for the border patrol agents using the roads for whom they were designed and built.

And indeed, these dangers are real. On a recent tour of the border wall in April 2011, Brown Field Station Chief Kelly Good showed us an area along the border patrol access road where an enormous boulder “the size of a car” had tumbled down the steep canyonside, hit the access road, and smashed through an entire 40 foot section of the border wall.

Washouts of the border wall caused by winter rains are clearly visible along the border wall in the mountains of San Diego County and have been documented in Arizona, most recently, at Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument in Lukeville, Arizona, the second major problem for this spot in three years.

Meanwhile, the in spite of the estimated $71 million dollars spent on this project, migrants looking for work have continued to find ways to enter the United States, Since 1994, migrants have largely been pushed eastward to cross through the seering heat of the Arizona desert, and over 5600 people have died.